People do not set out to fall in love and start families with any expectations that a barren abusive life or death awaits them. Of the victims that fall to emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and even physical harm, children never imagine or dream that such outcomes could befall them from the hands of those they love. Domestic violence/Intimate partner violence continue to take the lives of loved ones and leave others in dark captivity.

I remember my first true DV case several years ago.

I was working with a mom and dad that had 4 kids. Two of the children were in the living room and witnessed their dad smash their mother’s head into a wall and she fell “like a cooked spaghetti noodle on the floor” (what one of the children said as they tried to stifle their tears). The other two children were in a far back bedroom but could hear well enough to tell me what was said, the sound of their mom begging their dad to stop, and then a loud crash and a not so loud if a crash – and their siblings yelling and crying. The last thing they heard before the police sirens was their dad saying, “stupid b*&@# deserved it”.

I was not well prepared for what I would learn in the interviews with the children, and the history of how long the violence had been going on from family and friends. It was like an out-of-body experience listening to these small human voices describe, in a similar sense, what soldiers described to me when in counseling after a deployment in Iraq. These children even had the same 1,000 yard stare our soldiers demonstrated as they shared horrific events experienced fighting for our freedom. The contrast may sound drastic or improbable, but only to those that have never worked severe cases of DV/IPV. If you have worked this type of case, you know what I am talking about. It is an area of human behavior that I cannot for the life of me completely understand or explain outside the context of spiritual contexts. Children growing up in a battlefield called home.

DV/IPV does not discriminate based on color, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation

Over my career I have worked hundreds and hundreds of these cases. Some of the cases end with the aggressive and controlling partner changing and a couple staying together. Others split up, and in some splits the victim moves with the children moving to another state and changing their identity. DV/IPV does not discriminate based on color, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. Same sex DV/IPV can carry higher risk. How? Victims in same sex partnerships experience a severe lack of professionals believing they have been harmed, and transgender victims are more likely to be victimized in public. Children living in these homes are caught in the crossfire, can be weaponized against the victim, and are more likely to suffer irreparable harm over the course of their life.

This month is Domestic Violence Awareness month. We want to deeply reflect and remember the victims – our loved ones, friends, and neighbors that are counted as victims of domestic and intimate partner violence. Probability states that we all have a story to tell about ourselves or someone we know that has been harmed or still in danger presently. The REAL Academy hopes in this reflection a fire and passion are kindled to examine how to strengthen your skills as you work alongside children and adult victims and find professional channels to advocate for life saving change. In this post, we want to share some relevant facts to consider when engaging calls reporting DV/IPV, and some practice tips to remember while you are in the field to if you are a supervisor guiding your staff.

What is domestic violence/intimate partner violence?

Domestic violence and intimate partner violence extend past men beating on women. It is a constellation of offenses and crimes that occur in the home and among people who are related or who have, or have had, intimate relationships.

Domestic violence/Intimate partner violence can include harassment, emotional and psychological abuse, threats, violation of court orders (e.g., orders of protection, and no-contact orders), assault/battery, sex offenses, stalking, burglary, theft, embezzlement, destruction of property, kidnapping, child abduction, child abuse and homicide and related impacts (demonstrating fearfulness, concerned for safety, needing medical care, needing assistance from law enforcement, missing days of work/missing days of school). Many of these behaviors are precursors to more serious violence and impact the well-being of not only the immediate victim but also of others in the home.

Recognize the Facts:

- DV/IPV is 1 of 3 child maltreatment types that occur most often in child welfare complaints and investigations/family assessments

- Research suggests that in an estimated 30 to 60 percent of the families where either domestic violence or child maltreatment is identified, it is likely that both forms of abuse exist

- National survey showed that half of men who abused their wives also abused their children

- Research that examined the relationship between victims of domestic abuse and their relationship with their children show that they are more likely to use physical violence against their children than a parent who is not abused by their partner

- Children who both experience and witness domestic violence (opposed to those who just witness it) are worse off emotionally and psychologically

- A review of CPS cases in two States identified domestic violence in approximately 41 to 43 percent of cases resulting in the critical injury or death of a child

- 80-90% of children living in homes with domestic violence are able to give detailed accounts of the abuse (though parents think differently)

Based on the Child Abuse and Neglect User Manual Series: Child Protection in Families Experiencing Domestic Violence (2003) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children’s Bureau Office on Child Abuse and Neglect

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/domesticviolence.pdf

- More than 1 in 5 children surveyed (20.8%) witnessed a family assault, and more than 1 in 6 (17.3%) witnessed a parent assault another parent or their partner

- In the year prior to the survey, 8.2% of children had witnessed a family assault, and 6.1% had witnessed a parent assault another parent or their partner

- 25.6% experienced child maltreatment in their lifetime

- 13.8% had experienced maltreatment in the last year

Child Protection in Families Experiencing Domestic Violence (2nd ed.) (2018)

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/domesticviolence2018.pdf

Even more relevant facts:

- 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men experienced intimate partner violence (IPV).

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- 43.8% of lesbian women and 61.1% of bisexual women have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime, as opposed to 35% of heterosexual women.

- 26% of gay men and 37.3% of bisexual men have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, in comparison to 29% of heterosexual men

- Transgender victims are more likely to experience IPV in public

- Less than 5% of same sex couples seek a protective order

https://avp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2015_ncavp_lgbtqipvreport.pdf

Common bias we must examine:

- Victims are not just women and children

- Victims are not just in heterosexual relationships

- Children in ear shot are not impacted

- Children can learn to create norms in these environments and still be healthy/safe

- Aggressors/batterers cannot change

- Victims should have left earlier in the relationship

Interpret the effects on children:

- Witnessing domestic violence can have long-term and varied effects on children.

- Children may not sleep through domestic violence.

- They may hear the angry voices and their parent or loved one’s cries for help.

- They may see the damaged property and their parent or loved one’s injuries.

- Children may be sworn to silence or asked to lie for the abusers when the police arrive.

- Law enforcement states they often find children hiding under the bed or in the closet, or more dangerously, between the adults trying to stop an attack.

- Can impact children’s daily functioning.

- At higher risk of truancy and school dropout, emotional distress, guilt, health problems and delinquency,

- Significant long-term effects, such as PTSD, drug and alcohol abuse.

- 6 times higher risk for suicide and higher risk for intergenerational abuse as either victims or perpetrators of domestic violence.

- Strong link between children witnessing domestic violence and engaging in criminal activity as adults.

Agnew-Brune, C., Moracco, K. E., Person, C. J., & Bowling, J. M. (2017). Domestic violence protective orders: a qualitative examination of judges’ decision-making process; Naughton, C. M., O’Donnell, A. T., Greenwood, R. M., & Muldoon, O. T. (2015). ’Odinary decent domestic violence’: a disursive analysis of family law judges’ interviews; Turkel & Shaw, 2003. Domestic violence basics for child abuse professionals

Review relevant practice skills

Some child welfare states have a specific policy, practice protocol/standards, and tools to use for this occasion – make sure you check with your agency and are trained competently in using them.

When interviewing an adult victim keep in mind . . . some of these questions and work to talk to the victim alone.

- Has your partner physically harmed you in the past? Can you tell me what happened, when and where it happened – is anyone worried about you?

- Is your partner possessive? Are they constantly keeping taps on where you are, how long you are there, and who are you with?

- Does your partner seem to show a lot of jealousy that is more than “normal”? (A small amount of jealousy is normal and healthy) Do they accuse you of being unfaithful or isolate you from family or friends? If you answered yes to any of those, the jealousy might be the unhealthy and controlling type.

- Does your partner put you down/ belittle you? Do they talk negatively about your intelligence, looks, mental health, or capabilities? Do they say it is your fault they have violent outbursts and tell you nobody else will want you if you leave?

- Does your partner threaten you or your family with harm, isolation, or death?

- Does your partner physically or sexually abuse you? Have they ever pushed, shoved, or hit you, or make you have sex with them when you don’t want to? This is controlling and harmful to you even if it does not happen all the time.

Interviews with children: some brief starting questions – use open ended narrative technique to elicit natural responses (some states have adopted interviewing protocols, motivational interviewing, three-houses, or other evidence informed techniques)

Always start with building rapport and asking questions that are less invasive/intrusive and tell the child who you are and what you do/why you are there, which is to keep kids safe!

- Do your parents ever disagree? (Can also say argue – but stay away from words like fighting, and questions that are closed ended or Yes/No answer questions)

- What does that look like? Sound like?

- What do they disagree about?

- Do you know if they disagree every day/week/month? (you can think about the child you are interviewing and gage their age and stage of development to answer this question)

***Eliciting answers to these questions could quickly identify DV/IPV

- If you start with disagree – you can move to defining or asking the child to tell you the definitions of disagree versus arguing – and repeat the first 4 questions with arguing substituted.

- If the child has heard or seen arguing, ask them to try to tell you what their parents say and show you – include location “where did your parents have the argument? Where were you?”

- You may also want to ask about alcohol and drug use since it is often connected to DV/IPV cases.

DV/IPV in child welfare cases requires more discussion and training than what is in this brief article. We should always pre-plan with our supervisor, and teammates that have more experience to walk through what we will do when we get to the home. Try to think through the different ways the case could unfold in front of you. What if the children are not home? What if the victim is not allowed to speak to you alone? What if the aggressor will not let you in or is not home? What services for DV/IPV protection do you need to know about before you go out? Do you need to take law enforcement or another teammate for your safety and the families safety? Is this the first report on the family for DV/IPV?

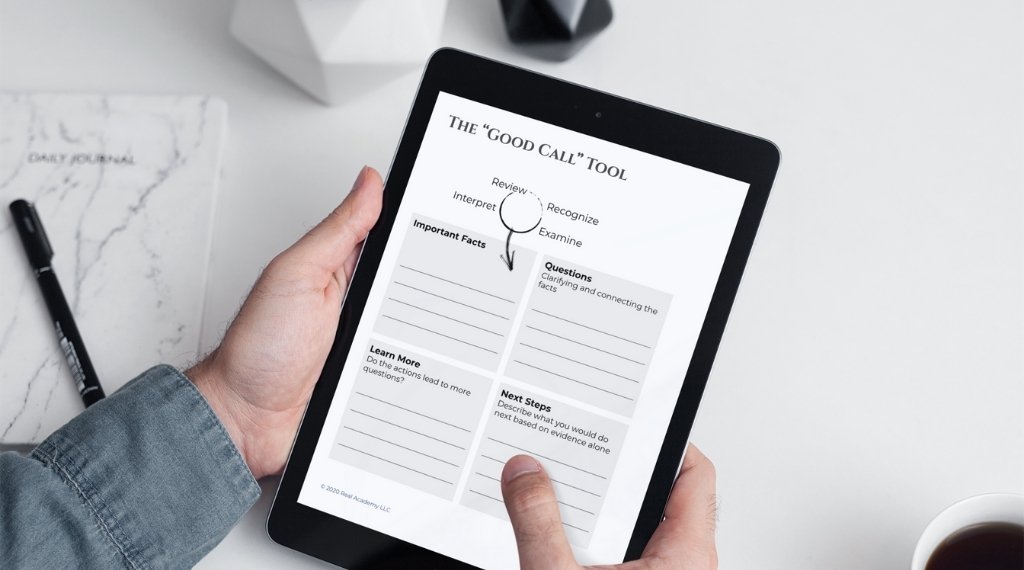

We owe the children, and the families respect enough to carefully plan our interventions. As you can see from the statistics DV/IPV cases can escalate quickly, and without notice. In this month of October, let’s make a commitment to making Good Calls™ with families suffering from DV/IPV issues by taking time to plan, use objective and open-ended interviewing techniques, and only allow the facts gathered in the case to guide the decision pathways.

Until next time. . .stay safe out there

Thank you for reading this article. We sincerely hope you found new information and encouragement at the same time. We have more articles and beyond that content that we are always working on in order to share with our students.